The Fayum Portraits: Meeting the Dead

Recently, I’ve been reflecting on how memories are kept alive through mementos – photos, portraits, notes, etc. These mediums may be used to preserve memories linked to people who are no longer in our lives. It’s fascinating how these items become personal or familial treasures, safeguarded in our homes or sacred places that hold deep meaning for us.

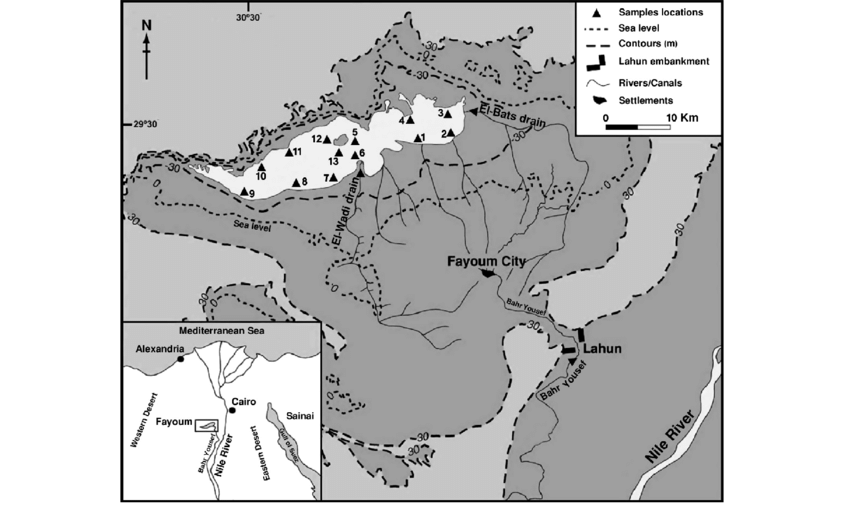

These reflections prompted an exploration into the role of funerary portraits from the Fayum region of Egypt, specifically those commissioned by Greek elites during the early centuries A.D. These portraits were more than mere artistic representations; they were integral to preserving the memory and status of the deceased.

During this period, Greek elites commissioned painted wooden panels that were meticulously secured within linen wrappings mixed with plaster, and then placed over the face of the mummified body. This practice not only honored the deceased but also signaled their wealth and social standing. The portraits, which were crafted with great care and detail, served as enduring tributes, capturing the likeness and spirit of the deceased. This funerary tradition ensured that their memory continued to resonate with the living, providing a lasting connection that transcended death.

Fayum Portraits Collage (1st to 3rd century A.D.)

New Funerary Traditions

The Fayum portraits are a fascinating testament to the blend of cultural beliefs about death and the afterlife that emerged in Egypt after its conquest by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C. As Greeks, and later Romans, settled in Egypt, they brought their own customs while also adopting local Egyptian traditions. By the second century A.D., when most of these portraits were created, Egypt had become a melting pot of various cultures.

As Greeks settled in Egypt, they adopted local mummification practices, which Egyptians believed to be crucial for the afterlife. However, instead of using the traditional relief masks that Egyptians placed on mummies, people of Greek origin opted to attach painted portraits to the mummified bodies.

Funerary mask from Abydos (4th century B.C.)

This practice led to the creation of the Fayum portraits between the 1st and 3rd centuries A.D. These funerary portraits, typically painted with wax-based paints on wood, were placed over the face of the mummified body, aiming to preserve the likeness of the deceased. Each portrait was akin to an idealized photograph of the deceased taken at the time of death, immortalizing the specific features of the deceased.

With about 900 known Fayum portraits, these images offer a remarkable glimpse into the diverse population of Egypt during this time. They depict people of all ages, captured in a strikingly lifelike manner, simultaneously featuring visual elements of Egyptian, Greek and Roman traditions.

Mummy of a Youth Called Artemidorus (2nd century A.D.)

Painting the Dead

For years, it was believed that the Fayum portraits were painted while the subjects were still alive and displayed in their homes as decorative items. According to this theory, the portraits were only later attached to the mummies. Some portraits even show signs of having been framed for display, suggesting that these individuals commissioned the portraits to adorn their homes as a sort of pre-death decoration.

However, this theory was challenged with recent discoveries. Researchers, using computed tomography scans of the mummies, revealed a surprising truth: many of the individuals depicted in these portraits died around the same age as they appear in their likenesses, suggesting that most of these portraits were only painted after their subjects had passed away. This new discovery adds a layer of mystery to the Fayum portraits, as we still don’t fully understand their religious significance, or the complete burial rites associated with them. What we do know is that these portraits likely evolved from ancient Egyptian funerary practices but were creatively adapted by a diverse and multicultural elite. Instead of being pre-death decorations, these portraits were probably posthumous tributes, designed to immortalize the features and memory of the deceased.

Mummy Portrait of a Woman (100 A.D.)

Immortalizing Status and Wealth

The mummification process preserved the physical body, while funerary portraits aimed to capture and preserve the soul. The Fayum portraits, created for the Greco-Egyptian elite of the Roman-administered Fayum Governorate, highlighted the deceased’s high social status. This conjecture is evident in two main ways: first, the elite's ability to commission these portraits, which required considerable financial resources and access to exotic materials, and second, the elaborate symbolism and detail within the portraits themselves.

Only the elite could afford the artistry and expensive materials required for these portraits. These portraits were painted on imported wood, including oak, fir, and yew from Europe, and cedar from Lebanon. The wax-based paints used in these portraits featured both local and exotic pigments, such as red pigment from Spain, showcasing the extensive trade networks accessible to the wealthy elite. Additionally, craftsmen employed gold leaf to enhance the appearance of jewelry and wreaths depicted in the portraits.

Lime Wood Mummy Portrait of a Woman (160–170 A.D.)

These portraits were designed to preserve and showcase the deceased's wealth and status even after death. The elite often displayed their wealth through elaborate gold jewelry and precious stones. Male subjects frequently wore wreaths made of leaves and flowers, symbols associated with military victory and eternal life in Greek and Roman culture. Female subjects were adorned with a variety of precious and semi-precious stones, such as emerald, carnelian, garnet, agate, amethyst, and occasionally pearls. Some portraits even feature intricate necklaces with stones set in gold. This ornamentation was intended to highlight the deceased’s achievements and status in life, extending their prestige into the afterlife.

In short

The Fayum funerary portraits are crucial in art history for their blend of Egyptian and Greco-Roman styles, vividly capturing the Greco-Egyptian elite of the Fayum region. These lifelike portraits, made with both local and exotic materials, reflect the wealth and cultural exchange of their time. They serve as enduring homages to the deceased and highlight the rich artistic and cultural interplay of this multicultural society.

Fun fact – According to a publication from the J. Paul Getty Museum, it appears that completed mummies, including their funerary portraits, might have been kept around the family home for some time before burial. They were sometimes displayed until they became neglected or damaged— possibly by children playing around them. Eventually, these mummies would receive a proper burial. This insight comes from the work of archaeologist Sir Flinders Petrie (1853–1942), who found mummies that had been worn and defaced, likely due to such household mishaps.