Representations of the Madonna-Whore Complex : A Feminine Paradox

I promise this post is not meant to alienate any male readers—pinky swear! That being said, this post dives into a topic that resonates deeply with the female experience: the Madonna-Whore Complex, coined by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud. This compelling duality reveals how women can be trapped in rigid categories—either the virtuous “virgin” or the seductive “vixen.”

Let’s be real: many of us girls have felt that pressure to fit one of these molds in the eyes of the men around us. The Complex suggests that these traits are mutually exclusive, forcing women to choose between being the nurturing and helpless feminine ideal—a figure “worthy” of bringing home to mom—or the daring, sultry woman who would not be considered a suitable wife. It’s a fascinating—and frustrating—exploration of how society views femininity, and it raises important questions about how female identity is perceived throughout history, particularly in art.

The Complex starkly illustrates that desirability and purity are often viewed as mutually exclusive. As Freud famously noted, "Where such men love, they have no desire, and where they desire, they cannot love." This post is truly intended as an exploration of how this concept has been represented in art history, revealing the societal implications and the ongoing struggle for a more nuanced portrayal of women.

A Flawed Conception of Femininity

Freud theorized that men with the Madonna-Whore Complex struggle to separate their love for their mother from their romantic feelings. Essentially, they believe women cannot be both nurturing and sexual. To cope with this conflict, they compartmentalize their romantic love: they cherish women they view as ideal wives and mothers but feel little sexual attraction toward them. Conversely, they often desire women they consider promiscuous, yet devalue them. In this dichotomy, women are confined to a rigid binary: they are either “good” or “bad,” leaving no room for nuance. Personally, I see the Madonna-Whore Complex as a reflection of misogyny; women who don’t fit the mold of purity and submissiveness are often labeled as “bad.”

Camerino’s The Madonna of Humility with the Temptation of Eve vividly illustrates this dichotomy. In the painting, the Madonna breastfeeds her child, embodying love and virtue. She is portrayed as nurturing, modest, and motherly, surrounded by both earthly and heavenly beauty.

The Madonna of Humility with the Temptation of Eve, Olivuccio di Ciccarello da Camerino (1400)

In stark contrast to the virtuous Madonna, Eve is depicted beneath her as a naked figure surrounded by darkness. Here, Camerino intentionally associates Eve with temptation and sin, emphasizing the Virgin’s purity against Eve’s fall from grace. According to the Biblical narrative, Eve embodies the ultimate perpetrator of sin. By allowing herself to be seduced by the serpent and raising the forbidden fruit to her mouth, she condemns humanity to an eternal ban from Eden. Ultimately, this scene serves as a perfect visual representation of the Madonna-Whore Complex.

Seduction Peeking Through Renaissance Art

The contrast between the Madonna and the whore permeates Renaissance art, though with added nuance. In works like Raphael's Madonna and Child, women are idealized as pure and virtuous, embodying the Madonna archetype.

Madonna and Child, Raphael (1503)

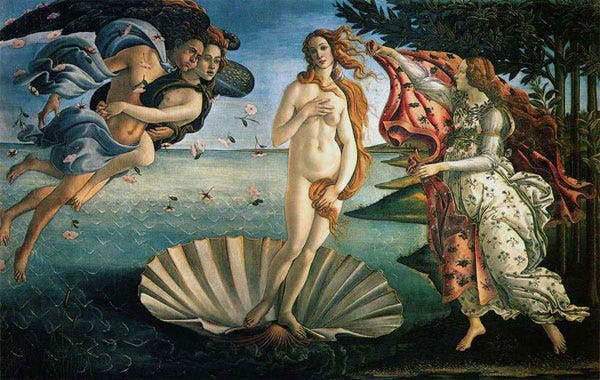

In contrast, Botticelli's Birth of Venus links women to desire, marking it as the first secular painting to incorporate nudity. Before Botticelli’s painting, nudity was primarily used in religious art to depict Eve's sin. In the Birth of Venus, Botticelli emphasizes the goddess’ nudity in a manner that is associated with beauty and myth, rather than sin and shame. The scene’s sensuality is amplified by the movement of hair and garments in the wind, adding a seductive touch and celebrating the beauty of the female form.

The Birth of Venus, Sandro Botticelli (1485)

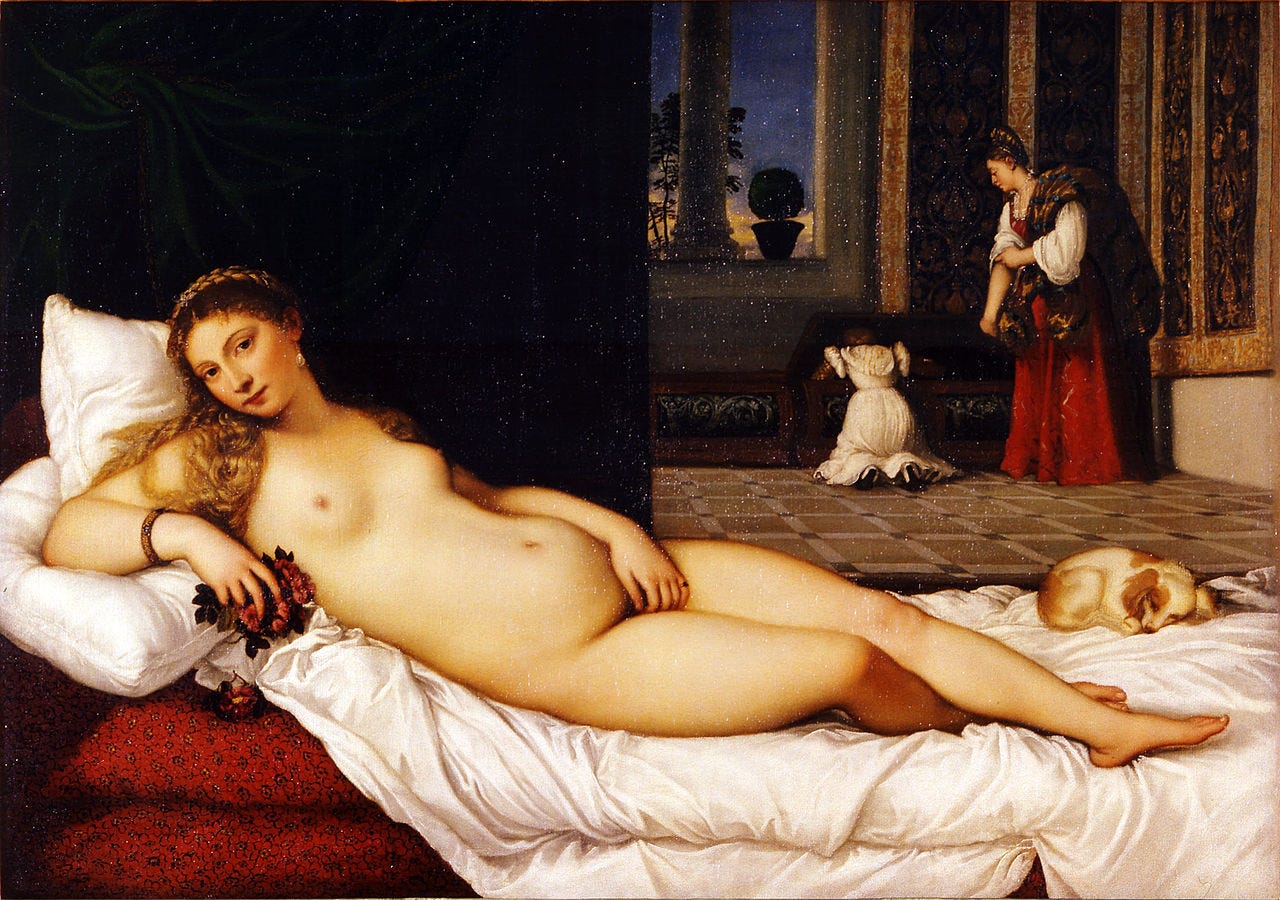

Botticelli paved the way for later Renaissance artists to explore the nude, as seen in Titian's Venus of Urbino, which embodies sensuality and allure, fitting the vixen archetype. Commissioned by the Duke of Urbino as a wedding gift for his younger wife, the painting’s evident sexualization of the female gender serves as a reminder of the bride’s marital duties. Here, the goddess of love is depicted as a sensual and alluring figure, daringly looking directly at the viewer, demanding their attention. This portrayal highlights the male desire for the vixen over the virgin, perhaps serving as another example of the Complex and the mutual exclusivity of virtue and desire.

The Venus of Urbino, Titian (1538)

Ambiguity in Baroque Painting

After the Renaissance, the lines between the virgin and the vixen became increasingly blurred. Baroque artists like Caravaggio delved into the Complexities of female identity, often depicting women who straddle the line between purity and seduction, highlighting the tension within the Complex. Notably, Caravaggio drew inspiration from all segments of Italian society, portraying both noblewomen and prostitutes in his work.

Caravaggio boldly challenged artistic norms to depict a more realistic view of female identity. In The Penitent Magdalene, he portrayed the Virgin Mary with the face of a known prostitute, accentuating her humility and remorse with a tear on her cheek. The courtesan who modeled for him met a tragic end, drowning in the Tiber. Under pressure to create The Death of the Virgin, Caravaggio reportedly had her corpse delivered to his studio, using it as inspiration for the lifeless Mary. Through his work, he blurred the lines between virgin and whore, illustrating how these opposing identities could coexist. This challenge to the Madonna-Whore Complex would resonate even more with artists in later centuries.

Penitent Magdalene, Caravaggio (1594-1596)

The Death of the Virgin, Caravaggio (1602-1606)

A Modern Challenge to the Complex

Modern artists like Gustave Courbet challenged traditional representations of women. In works like La Source, he overtly sexualizes the female form, challenging 19th century standards of piousness and virginal virtue. Similar to Caravaggio, Courbet championed realistic depictions, portraying people and their lives with raw honesty.

Courbet rejected the ideal and unattainable, expressing a deep distrust of the ruling class and authority. He aimed to challenge the fake standards of his time, portraying life as he saw it, no matter how unappealing. His paintings were meant to resonate with viewers, making realism his defining style. This is especially evident in his depictions of women, where their nakedness subverts traditional academic nudes by defying expected female roles. Courbet’s nudes challenge rigid 19th century Victorian ideals of female passivity, asserting that women possess their own sexuality and breaking away from the normative standard of the asexual woman.

La source, Gustave Courbet (1868)

Contemporary Critiques of the Madonna-Whore Complex

Moving into the contemporary era, artists like Cindy Sherman challenge and deconstruct traditional female archetypes - WIN! Sherman’s photography dives deep into the commonly observed roles women play in 1960’s society. Her photography is considered a product of the emerging feminist movement of the time, which aimed to raise awareness about female sexuality, and broaden women’s rights with respect to sexuality, work, and domestic life. Ultimately, Sherman’s work serves as a critique of the male gaze and its influence on female behavior.

In her iconic piece Madonna, Cindy Sherman dons classic feminine attire, including an elegant robe and a delicate headscarf. She glows under the light, posing in a way reminiscent of the Virgin Mary beneath a halo, similar to biblical paintings. This pose critiques the idealized representations of women in art from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. By replicating these historical images, Sherman highlights the clichéd portrayals of femininity and the cliché associations between womanhood and purity, grace, and innocence. Interestingly, Sherman’s photography often depicts characters like the girl next door, the damsel in distress, and the housewife, further critiquing the narrow representations of women in contemporary times.

Final Notes

This exploration of the Madonna-Whore Complex and the representation of women throughout art history has uncovered gender biases and shifting views of femininity with time. From the rigid binaries of the Renaissance to the blurred lines of the Baroque and the bold critiques of modern artists like Sherman, these portrayals reveal deep societal implications. While the archetypes of the virtuous “Madonna” and the seductive “whore” persist, artists have increasingly challenged and deconstructed these simplistic views.

By highlighting the complexity of female identity, these works not only reflect individual experiences but also critique the cultural norms that restrict women to narrow roles. As we continue to seek a more nuanced portrayal of femininity, the ongoing dialogue around these archetypes remains vital. In doing so, we open the door to a richer understanding of women's true identities and experiences, moving beyond outdated stereotypes and a more realistic view of femininity.